words Deb C

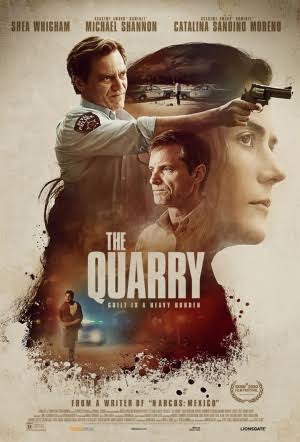

Directed by Scott Teems, the ambiguously titled The Quarry, quickly becomes clear that it is both human and actual.

Personal narrative and feeling seem to be buried deep and communication struggles to break through and fails, generally speaking. The original novel, by Damon Galgut, was based in the endless veldts of Africa, a harsh place where surviving the desolate setting could only emphasise the conflict created by the human animal. Whereas this Indie movie has been set in small town West Texas, America, close to the border. The only apparent conflict created by man himself, the usual litany of murder, racism, betrayal etc, etc.

The town of Bevel has few visible inhabitants. The action moves between the sparsely furnished church, police station, the quarry and the house where the minister rooms. Apart from the slowly growing congregation( mainly of mixed race and underprivilege), the characters are limited to “David Martin” the false minister (Shea Whigman), Chief of Police of the chiselled chin(Michael Shannon) and his two subordinate, bully boys, Celia,( Catalina Sandino Moreno) the housekeeper and part time lover of the Chief of Police (too often making her appearance in her dressing gown), and the two young Mexicans(Bobby Soto and Alvaro Martinez) , soon to bear the blame for a gringo’s crime.

The fugitive (who remains nameless) is on the run for his crimes (arson and murder) and compounds these sins with the murder of the good Samaritan, a minister who attempts to help him both physically and spiritually,”You can talk to me…” This nameless one continues with his inability to communicate truly unless it is in his sermons where he preaches to the small congregation in Bevel in the character of his assumed minister’s identity. His preachings are simply taken from The Bible and reflect what we know as his real situation, ”I am a sinner.” True but misdirecting, and the Chief of Police and his attitude to ”just another illegal” fails to follow up on his unease and the clues that could save the life of the innocent accused.

Despite being haunted by flash backs of a burning building and his confinement in what seems to be a coffin the audience finds little to empathise with. The use of over shoulder camera shots seems to help, or hinder, this sense of distance. Personal conversations with the housekeeper are the only moments where “David” shows a more caring nature. He is typically closed off in his solitariness and refusal to share anything of himself.

His Damascus moment in court is his last chance for redemption, but like Peter (The Gospel of John 18:13–27 ) he is not able to state the truth as demanded “Before the rooster crows today, you will disown me three times. And he went outside and wept bitterly”. The nameless one follows in his inability to follow the dictates of his conscience and disowns his own identity three times, symbolically shrugging off his cassock as he exits into the darkness and retribution.

This film was intermittently intriguing in its attempt to show a deeply flawed antagonist, troubled by his inner urging to cleanse himself of sin and his inability to do so. For this viewer, there was too much silence and not enough translation for mere mortals. (From Rumi’s words “Silence is the language of god.”)